US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: can States lead the fight to reduce carbon emissions?

On June 1, 2017, the United States – the world’s second biggest greenhouse-gas (GHG) producer after China – announced that it intended to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Should they do so, they will not only refuse to reduce their emissions, but they’ll also cease contributing financially to help developing countries adapt to climate change and participate in the mitigation effort.

The US had committed to reduce its GHG emissions by 25% to 28% by 2025 compared to 2005, which is equivalent to 5 Gt CO2-eq. less per year. They also pledged to allocate $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund to help developing countries, and have already contributed $1 billion. However, they will no longer participate after the current commitment period, ending in 2018. Paris Agreement signatories have overall committed to a $100 billion contribution per year up to 2025.

In fact, the withdrawal from the agreement cannot be notified officially before November 4, 2019, and will only be effective one year after notification. Nevertheless, Donald Trump’s announcement was clear: at the federal level, decisions made by the previous administration on climate change mitigation are not going to be applied, starting from 2017.

Wider negative consequences

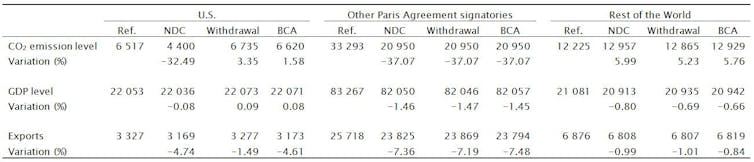

The context around this policy change is wider, however: the United States will not constrain their emissions, whereas other main emitters will. Lower emissions are mainly achieved by reducing use of fossil fuels, leading to a lower price for the latter at the world level. As a consequence, the US will even be encouraged to consume more fossil energy and to slow the pace of transition to less GHG-intensive energy sources, increasing their emissions all the more. In addition, the most constrained industries in signatory countries may relocate to the United States. Our simulations show that, because of these two effects (the former being quantitatively larger than the latter), by leaving the Paris Agreement, the United States would emit 2.3 Gt CO2 more – the equivalent of all CO2 emissions by India and Brazil in 2011 – than if they had respected their commitment. This corresponds to 218 Mt more than in a world without any agreement. At the world level, US withdrawal increases carbon leakage of the Paris Agreement by 40%, going from 5.1 to 7%.

The withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, by preventing the implementation of a carbon tax (or any other equivalent measure) to limit CO2 emissions, allows the United States to increase their production by 0.17% in 2030, corresponding to 37 billion USD. However, this figure does not take into account potential impacts of climate change on production (e.g., extreme events impact on agricultural production, or conversely, carbon fertilization), nor externalities of production technologies on the environment or human health.

One of the instruments often considered to reduce carbon leakage is a border carbon adjustment (BCA). It consists in taxing imports from unconstrained countries on the basis of the GHG emissions they cause, for instance using the same carbon price as in the importing country. If all Paris Agreement signatories were to impose such a tax on imports from the United States, it would reduce US exports by 104 billion USD in 2030 (-3%), but would only negligibly impact US emissions (-115 Mt, equivalent to -1.7%). This low impact is due to the fact that US production is mainly oriented toward its sizable domestic market. In addition, the BCA would have a negligible effect on the GDP of signatory countries. Put differently, a border carbon adjustment would only be a political signal to the United States with small environmental or economic effects.

States can take the lead

President Trump’s announcement does not completely prevent any US federal policy against climate change – in particular it does not preclude policies supporting environment-friendly innovation – but the hope mainly lies on what American states are willing to do, independently from the federal government. States still have the possibility to regulate high-emissions sectors, in particular power production and transportation. They can impose carbon prices, electricity prices, taxes on gasoline use … and constrain energy-generation processes. Some states are already engaged in self-determined GHG reductions. For example, nine north-eastern and mid-Atlantic states are part of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, with an objective to limit CO2 emissions from the power sector. California participates in the Western Climate Initiative along with Canadian provinces, to limit by 2020 its GHG emissions to the level observed in 1990.

In response to President Trump’s announcement, several states (16 as of today, representing 23% of total US emissions) formed the United States Climate Alliance and committed to uphold the US objectives of the Agreement within their borders. The UN Secretary General’s Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change, Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City, wrote to the UN Secretary General to ask UNFCCC Parties to acknowledge subnational commitments, from states, cities, businesses and civil society, as a parallel submission to the Paris Agreement. Some of these actors are also making their pledges to the UN platform NAZCA, which brings together commitments to climate action by actors other than sovereign states.

The American states making commitments are not the largest emitters (they represent 23% of U.S. emissions, but 42% of U.S. GDP), and their abatement costs (the cost of decreasing emissions by one additional unit of CO2-equivalent) are often higher compared to other states. Nevertheless, despite the fact that they cannot compensate a lack of federal commitment, their actions send a strong signal to the international community and the rest of the United States. They may also be able to construct new economic models accounting for climate externalities.

Supporting mitigation efforts

Other signatories of the agreement should support these actions, for example, by inviting states to join existing carbon markets. They will also have to find new financial resources to achieve the Green Fund objectives, as supporting mitigation and adaptation in developing countries is a major concern for both climate change and development. Mitigation actions may also be facilitated by technological advances, such as the sharp decrease in the cost of renewable energies. In the end, the transition to non-fossil fuel energy sources will happen, but at a slower pace than with a strong federal commitment.

Impact of the Paris Agreement, the U.S. withdrawal and retaliatory BCA in 2030

GDP and Exports are labelled in 2011 USD billion; CO2 emissions are in million tons. Variations in percentage change represent the difference between the considered scenario and a world where no climate mitigation agreement is enforced (“Ref.”). Three scenarios are considered, in addition to this reference scenario: the “NDC” scenario (for “Nationally Determined Contributions”), in which all Paris Agreement initial signatories achieve their emissions reduction commitments; the absence of the U.S. of this agreement (“Withdrawal” scenario) ; as well as a potential reaction of other signatories of the agreement through a carbon tax on their imports from the U.S. (“BCA” scenario, for “Border Carbon Adjustment”). Authors calculations.

![]() For more details, see the Lettre du CEPII N°380 (in French).

For more details, see the Lettre du CEPII N°380 (in French).

La version originale de cet article a été publiée sur The Conversation.